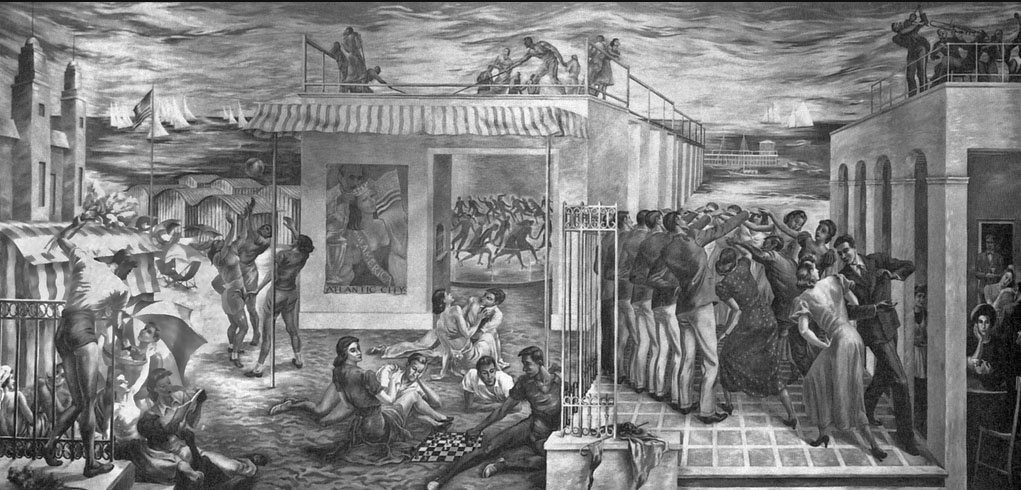

Atlantic City, NJ Post Office 'Youth' – oil on canvas. © Library of Congress.

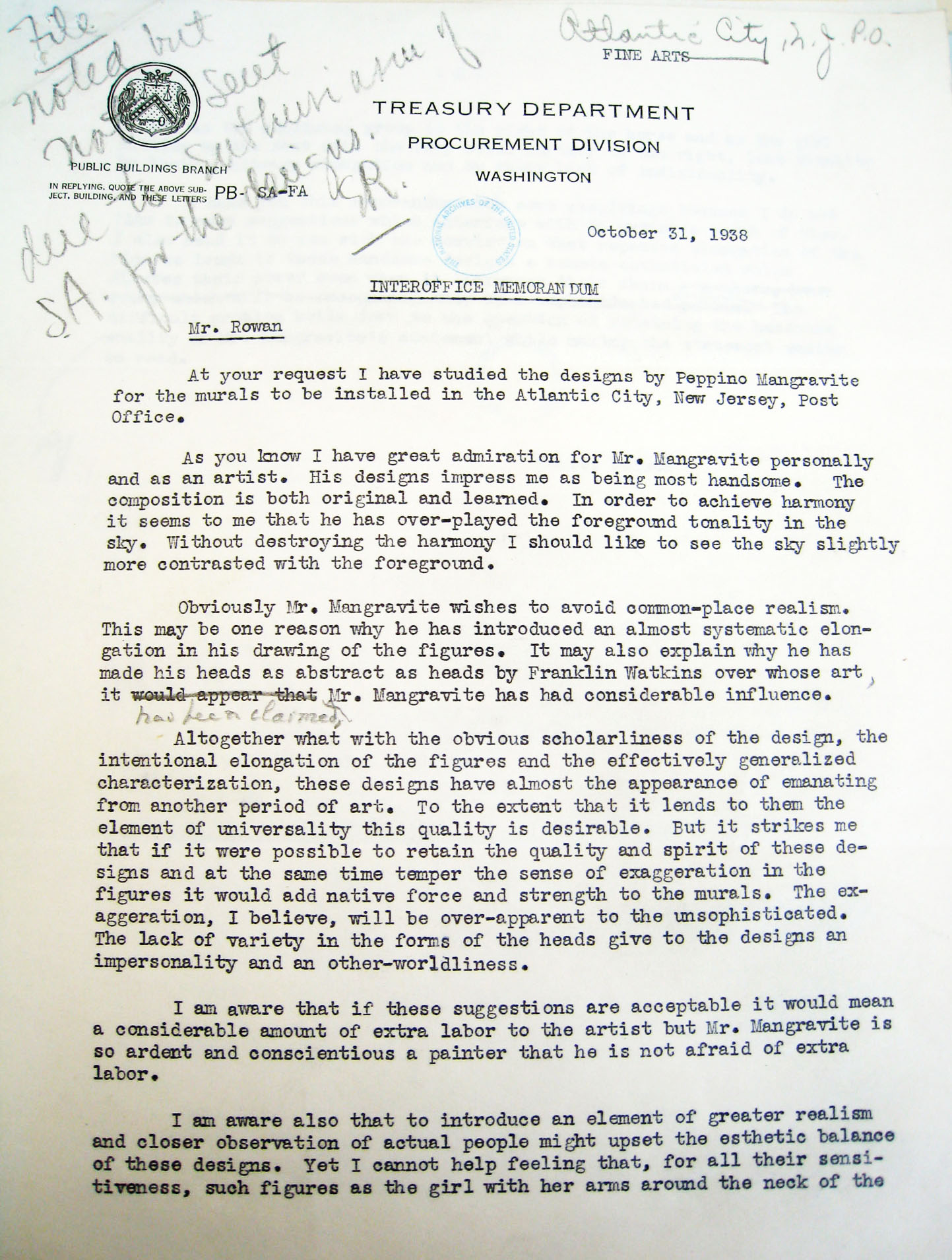

Letter to Edward Rowan This document is in the collection of the National Achieves at College Park (NACP), College Park, MD, in Record Group 121 (Records of Federal Works Agency. Public Buildings Administration. Section of Fine Arts. (1939 - 1949) (Most Recent)Department of the Treasury. Procurement Division. Public Buildings Branch. (06/10/1933 - 07/01/1939) (Predecessor), Correspondence of Officials, Compiled 1934 - 1943), Inventory Entry 133 (Section Case Files NH - NJ), Box 66.

Atlantic City, NJ Post Office 'Youth' – oil on canvas, Peppino Mangravite (1939) Images courtesy of the USPS

Photographs taken by Ira Youtie.

Atlantic City, NJ Post Office was demolished in 2010 however the murals were saved. Conversation was done on the two murals by Parma Conservation in Chicago, this is an image of the restored mural wrapped and waiting to reinstalled at a new location. Photograph taken in 2012 by Jimmy Emerson.

As Mangravite's second mural commission the design process was very different when compared to Hempstead, New York which had been his first for Section. In contrast to the rich history Hempstead offered Mangravite to work from, Atlantic City was a relatively new city. The archives offer no record of letters suggesting mural topics for this commission. The result being that his Atlantic City murals show little which can be claimed as authentically Atlantic City in the murals. Even so it was an image that both the locals and the tourists understood could connect with the city.

Just as he had with Hempstead, Mangravite painted two panels for the Atlantic City post office; Youth and Family Recreation. Together the panels depict more than 130 figures participating in a range of seaside activities.1 The Section mural descriptions do their best to capture all the activity;

“Youth: This composite design depicts young people enjoying the recreational activities of Atlantic City. At the left a vender sells flowers and fruits to sun bathers while others play hand ball. In the center foreground a chess game progresses and behind this is a pavilion with roller-skaters. On the wall of the building is a poster of "Miss America" and on the roof are shuffle-board players. To the right, on the terrace of a cafe, several couples are dancing a square dance while an orchestra plays on a roof above.”

“Family Recreation: This composite design depicts children and their parents enjoying the recreational activities of Atlantic City. Children are rolling hoops and riding ponies. In the center background is a merry-go-round and in the foreground a family group relaxes peacefully. At the right children play a game of blind-man's bluff while a mother tends to her young daughter and a husband adjusts the visor of a beach chair for his wife. Adult groups enjoy the sun decks of the roofs and in the marine background are sailboats.” 2

To illustrate the frantic pace of the resort Mangravite filled the frame with activities, each seeming to stack on top of another towards the high set horizon. Even the glimpses of the ocean beyond the sand include handfuls of boats with white sails. The figures are all activity spending their time by the sea, even the families relaxing in the sand are in conversation or doing other activities. The buildings, patches of sand and promenade further the feeling of a hectic pace as they all blend together. Their edges only partially defined as they disappear behind the next activity in the scene. This resort imagery is missing the roller chairs, Atlantic City’s distinct boardwalk pattern, the lighted signs, the shops and exotic boutiques and numerous iconic buildings which made up the unique nature of Atlantic City.3 In all the action displayed, only one element connects the two seaside scenes to Atlantic City, the poster for Miss America.

What Mangravite depicted was the busy, carefree image of middle-class America enjoying a vacation at the shore before the Depression. It taps into the period of time when Atlantic City was the “Queen of Resorts.” The murals along with the recently revived Miss America fits perfectly here as a part of the economic success the city experienced in the 1920s.

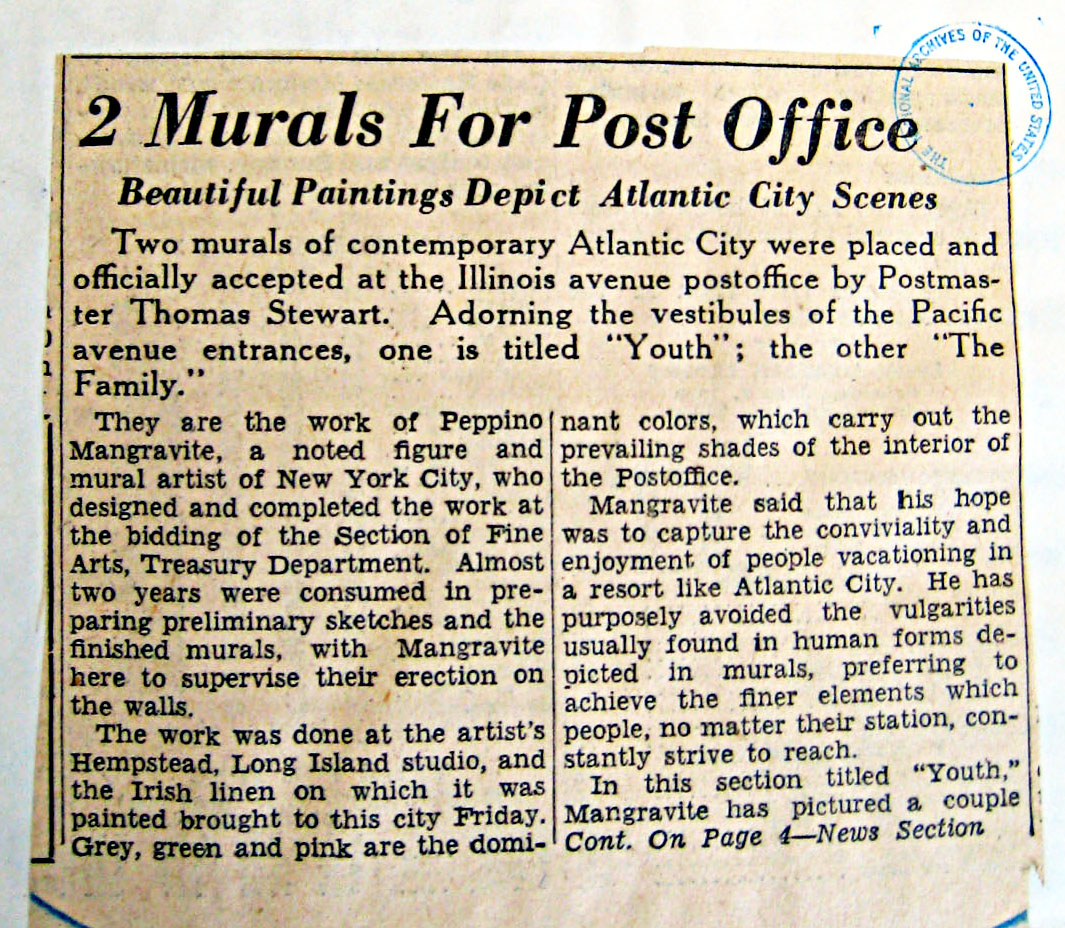

Newspaper clipping about Mangravite's mural installation from the June 4, 1939, Atlantic City Press.

After the mural was installed the Atlantic City Press wrote

“Mangravite said that his hope was to capture the conviviality and enjoyment of people vacationing in a resort like Atlantic City. He has purposely avoided the vulgarities usually found in human forms depicted in murals, preferring to achieve the finer elements which people, no matter their station, constantly strive to reach.”

It is important to note that the article quotes Mangravite as saying LIKE Atlantic City. By painting the generic resort Mangravite could erase the signs, lights, billboards and commercialism, illustrating the resort image that tourists told their families and friends about. What remained was the middle-class American enjoying the leisure time he was rewarded for his labor. While the tourist looking at the mural would have seen the resort family-friendly idea, the locals would be reminded of the idea that anyone could make it big on the boardwalk. The people of Atlantic City saw the enjoyment in the murals and as Mangravite installed the two scenes people stopped to talk with him. He passed these messages on to Rowan in a letter, "one colored woman wanted to know what chapter of the bible the murals represented" another patrons comment led him to suspect that "probably he will complain to Hitler about the murals, on the grounds that the American people have no right to be so happy and have so much freedom and good times." Rowan wrote back that it was "quite remarkable, and reflects the joy that you have caught in the work."4

In the middle of all the generic seaside fun Mangravite hung a poster for the Miss America pageant, the one arguably commercial aspect specifically associated with Atlantic City. Mangravite was not painting our concept of the modern day Miss America; he was painting the 1930s Miss America, complete with American flag in hand. The Miss America pageant had started in 1921 by the Atlantic City Chamber of Commerce as one part of the Labor Day festival.5 Atlantic City businesses were looking to stretch the summer business one more weekend and a Labor Day weekend festival complete with pageants for both sexes of all ages, parades along the boardwalk with floats, evening balls and other events was organized. The “Miss America” pageant was only one element. For many years it was not a structured competition between states each with their own organized pageants instead in the 1920s several newspapers in east coast cities sponsored city level beauty contests. Women entered by mailing in a photograph to their city newspaper.6 The local papers offered a prize of the chance to participate in the Atlantic City pageant, including a trip to Atlantic City. The competition was open to young women with no prior modeling or pageant experience. The Labor Day festival was a huge financial success. It served as an example of the entrepreneurial spirit of the American Dream rooted in Atlantic City.

Miss America 1939, Patricia Donnelly from Detroit, Michigan. © 2013 Miss America Organization All Rights Reserved

The pageants stopped in 1927 and the current pageant returned to Atlantic City in 1935 and once again it served as a commercial tool to increasing business at hotels and travel to the resort city. Many of the parades, events and balls remained as they had in the 1920s but this time it was titled “The Showman’s Variety Jubilee.” Later it was officially changed to “The Miss America Pageant.”7 This confusion of the name is clear as the names “Miss America” and “Miss Atlantic City” were both referenced in letters between Rowan and Mangravite in discussion of the murals. While Miss America did become the descriptor in the discussion of the murals, the commentary on the inclusion or the depiction was restricted to one comment from Rowan to Mangravite that “the poster of Miss Atlantic City should be treated in such a way, subdued possibly, that it does not detract from the attention which belongs to the neighboring figures in this composition.”8 No matter the title the revival of the pageant had worked. During Labor Day weekend Atlantic City was again filled with tourists as word spread across the country thru pre-movie newsreels. Karal Ann Marling in her book Wall-to-Wall America, concedes that the inclusion of the “poster was an appropriate emblem of local prosperity and propriety.”9

Newspaper clipping from the June 4, 1939 Atlantic City Press. This document is in the collection of the National Achieves at College Park (NACP), College Park, MD, in Record Group 121 (Records of Federal Works Agency. Public Buildings Administration. Section of Fine Arts. (1939 - 1949) (Most Recent)Department of the Treasury. Procurement Division. Public Buildings Branch. (06/10/1933 - 07/01/1939) (Predecessor), Correspondence of Officials, Compiled 1934 - 1943), Inventory Entry 133 (Section Case Files NH - NJ), Box 66.↑

The official description of the Atlantic City murals as issued by the Section. Record Group 121: Inventory Entry 135 (Letters Received Concerning Completed Work), Box 1.↑

Information on Atlantic City in the 1920s and 30s taken from Charles E. Funnell, By the Beautiful Sea: The Rise and High Times of That Great American Resort, Atlantic City (Rutgers Univ Pr, 1983); Vicki G. Levi and Lee Eisenberg, Atlantic City: One Hundred Twenty-Five Years of Ocean Madness, 2nd ed. (Ten Speed Press, 1994); Bryant Simon, Boardwalk of Dreams: Atlantic City and the Fate of Urban America (Oxford University Press, USA, 2006).↑

Carbon copy of Rowan's letter to Mangravite dated June 12, 1939. This document is in the collection of the National Achieves at College Park (NACP), College Park, MD, in Record Group 121 (Records of Federal Works Agency. Public Buildings Administration. Section of Fine Arts. (1939 - 1949) (Most Recent)Department of the Treasury. Procurement Division. Public Buildings Branch. (06/10/1933 - 07/01/1939) (Predecessor), Correspondence of Officials, Compiled 1934 - 1943), Inventory Entry 133 (Section Case Files NH - NJ), Box 66.↑

Ann-Marie Bivans, Miss America: In Pursuit of the Crown: The Complete Guide to the Miss America Pageant, 1St Edition (Master Media Pub Corp, 1991).↑

Candace Savage, Beauty Queens: A Playful History (Douglas & McIntyre Ltd. (Canada), 1998), 16.↑

Elwood Watson and Darcy Martin, “The Miss America Pageant: Pluralism, Femininity, and Cinderella All in One,” Journal of Popular Culture 34, no. 1 (Summer 2000): 109.↑

A letter dated February 27, 1939 was the only instance in which any comment on the inclusion of Miss America was ever discussed. Marling (Marling, Karal Ann. Wall-to-Wall America: Post-Office Murals in the Great Depression. Univ Of Minnesota Press, 2000, page 266) writes in her book that “When Rowan warned Victor Arnautoff against “bathing beauties,” he had this lush Miss America in mind” and Melosh (Melosh, Barbara. Engendering Culture: Manhood and Womanhood In New Deal Public Art and Theater. 2nd prt. Smithsonian Press, 1991, page 160) focuses on Rowan’s use of the word subdued in her book. She does not place it in the context of the complete sentence, which given the stacking of images in the mural the idea that one element would need to be subdued to not over power another would be an important factor – Miss America or not. Record Group 121: Inventory Entry 133 (Section Case Files NH - NJ), Box 66.↑

Marling, Karal Ann. Wall-to-Wall America: Post-Office Murals in the Great Depression. Univ Of Minnesota Press, 2000, p. 267↑